Sanctum Tathaa: A Heritage Established in 1498

Sanctum Tathaa (मन्दिर तथा) was founded in 1498 CE by Khenpo Dechen Gyatso, a Nyingma master from Yaqing, Kham. At the invitation of the Lo Gyalpo (ལོའི་རྒྱལ་པོ་), he undertook a three-year retreat in the remote Yazegang valley. According to inscriptions preserved at the site, he received a vision of Padmasambhava during profound meditation, prompting him to establish a hermitage and temple beneath a towering cliff.

The original monastery comprised only a main assembly hall and a solitary monk’s cell, devoted to Nyingma teachings while integrating elements of Bön ritual. In the late 16th century, the core structure was expanded with the addition of a consecrated fragrance chamber and a dedicated retreat cell. In the 18th century, ritual exchange was initiated with monastics from Ladakh. By the mid-19th century, during the Gorkha invasions, portions of the complex were destroyed, resulting in the loss of numerous texts and murals. Circa 1825, following pervasive social disruption and an earthquake-induced collapse, Lopön Gonpo Rangpa successfully led a comprehensive reconstruction.

During the 1960s, centralization policies of the Nepalese kingdom temporarily halted all proselytizing activities, leading to the monastery’s temporary disuse. Restoration efforts commenced in 1997 under the guidance of the current spiritual seat holder.

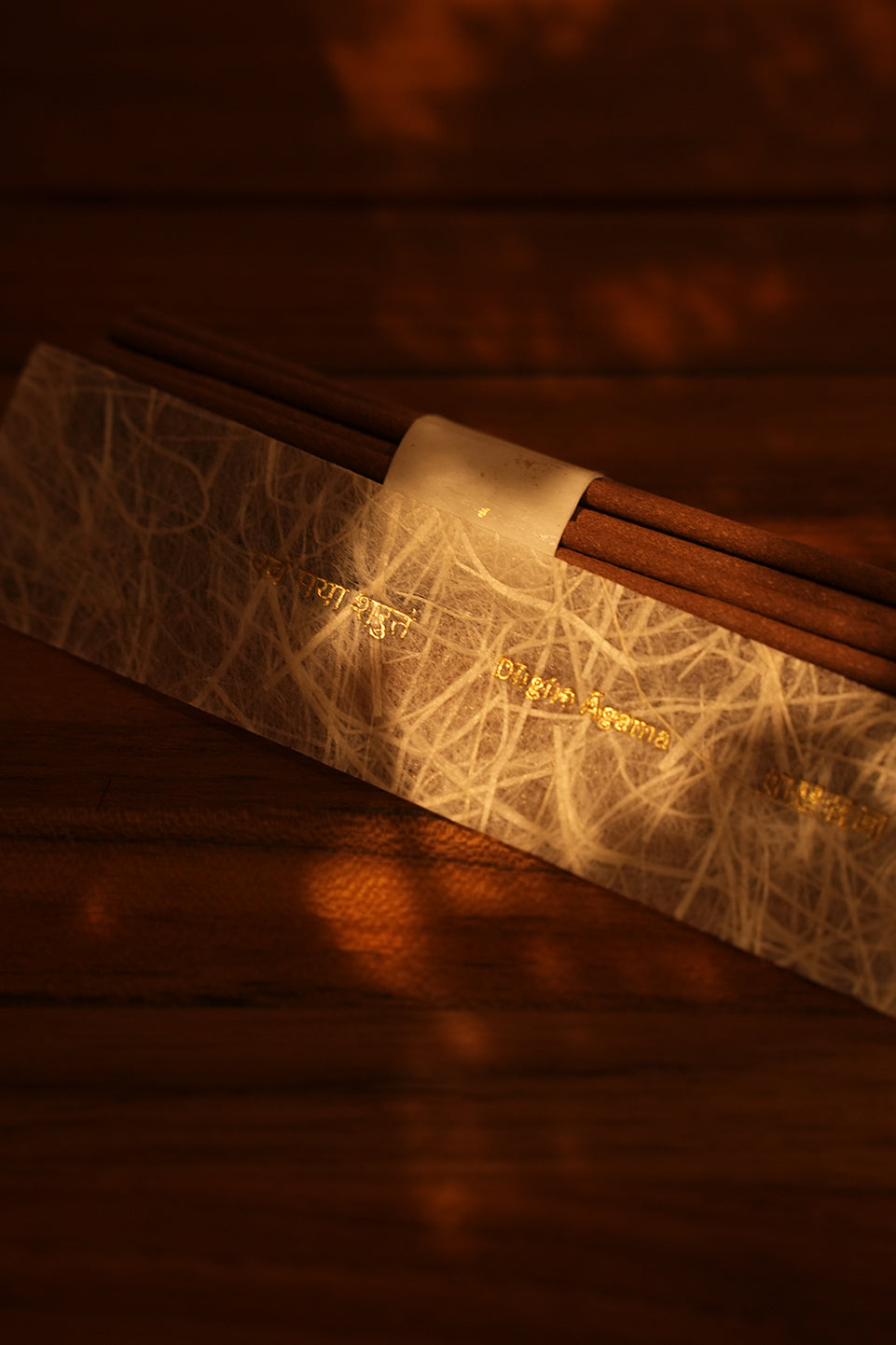

Today, Sanctum Tathaa is renowned as a key spiritual site in northern Mustang. Though severely damaged in the 1934 Bihar–Nepal earthquake and a subsequent fire, it has been gradually restored. It receives several hundred pilgrims annually and is particularly recognized for preserving its unique traditional incense practices.

A Succession Woven from Silence and Stone

Since the monastery’s consecration in 1498, Sanctum Tathaa has adhered to the core principle: “No reliance on reincarnation, only upon realization.” Consequently, the passage of its abbatial seat has become a unique historywoven from sacred oral transmission and stone inscriptions. After the founder Dechen Gyatso witnessed three radiant apparitions of Padmasambhava in the Yazegang ravine, he inscribed in his own blood upon the cliff the Founding Vow: “The seat belongs not to one man; the lamp must pass to a thousand lamps,” thereby establishing the custom of elective succession.

Nearing death, Gyatso entrusted his robe, the bell-and-vajra, and a crimson seal to his chief disciple Chökyi Dorje, who subsequently transmitted them to his nephew Jampel Gyatso, thus inaugurating an early tradition of uncle-to-nephew succession. By the time the seventh abbot, Rinchen Namkha, saw the Gorkha armies sweep through the valley and the temple doors consumed by fire, he fled into the snow ranges with the seal clasped to his chest; three years passed with no word. The remaining monastics maintained the precepts beneath an “empty throne,” ritualistically placing the bell and vajra upon the vacant seat each dawn and dusk to ensure the lineage remained unbroken.

Then in 1825 the wandering reciter Könchok Namdrol discovered the bones of Rinchen Namkha, who was still clasping the seal, in an ice-cave. Namdrol carried the cracked bell back to the ruins. The community purified him with spring water, and Namdrol was enthroned as the eighth abbot. He immediately re-erected the temple hall on the rubble and instituted the “cavern ordeal”: every new abbot must spend seven winter nights in sealed retreat; only if confirmation is received through dreams or the spontaneous ringing of the bell may he ascend the throne.

In the late nineteenth century the ninth abbot Sonam Wangdu, versed in the arts, hewed a “perfume chamber” beside the retreat cave, thereby integrating the secret incense formula with the tantric liturgy. Consequently, the abbatial seat came to embody both “dharma succession” and “aromatic succession.” During the 1920s the tenth abbot Ngawang Chökyi travelled to Drepung Monastery in Lhasa and was awarded the degree “Lopön”; upon his return he erected the lecture hall and replaced the succession system with the “Khenpo Council.” Annually, on the tenth month of the Tibetan calendar, the ten Khenpos convene in the protector chapel. A copper bell is shaken three times over inscribed lots, and the name that resonates becomes the successor. This rule endured until 1959, when Nepal’s centralization decrees forced the temple to close; the bell and vajra were locked in a cedar chest, and the throne hung empty once more.

The Meaning of Tathaa: Philosophy and Psychological Grounding

Tathaa (तथा) translates to "just as it is,"a concept that echoes the ancientSanskritphrase from theDīgha Nikāya(Long Discourses) of the third century BCE:evaṃ mayā śrutaṃ—"Thus have I heard." For Sanctum Tathaa, incense ismore than a mere historical and spiritual legacy; it is acontemporary expression of a two-millennia-old philosophy and a vital source of psychological grounding for daily life.

Tathaa's Purpose

Amid the clamor of modern life, Sanctum Tathaa strives to restore the delicate yet authentic link between people and the inner realm. Rooted in the millennia-old teaching of tathā—“just as it is”—we translate incense-making, aspirations, and protective mantras into gentle, accessible vessels. Through our products and guidance, we bridge traditional contemplative practice with contemporary living, connecting valley communities and restless city dwellers alike. Our offerings are designed to help others cultivate self-order and deepen their inner coherence. Sanctum Tathaa does not proclaim divine edicts; it quietly echoes the ancient refrain, “Thus have I heard.”